|

A Book Review

by John L. Godwin

In late August, Americans in the nation’s capital commemorated the March on Washington, forty years after the event that took place in the summer of 1963. It was there that Martin Luther King, Jr. rendered his famous “I have a dream” speech, whose eloquent words were marked with a plaque at the Lincoln Memorial. This stirring occasion, along with the crucial civil rights campaigns at Birmingham and later at Selma, Alabama, through which a powerful impetus for reform was exerted, led to the passage of major civil rights legislation by U.S. Congress. The genius of King’s leadership became instrumental in the movement that culminated in those enactments of 1964 and 1965, establishing the legal groundwork for a new era of civil and racial equality in America. But a lot has happened since the 1960s. Time enough has passed for a new generation to come of age in an era of conservatism, developing new perspectives on the revolutionary movements that changed America through the years leading up to the Nixon groundswell. At least four conservative presidencies have left their mark on America— Nixon, Reagan, Bush I, and Bush II. Southern Republicans proclaiming conservative ideologies have become among the most visible figures in American politics. And among conservatives, the 1960s has been routinely denounced as an era of “hippie revolt,” a time when irresponsible young people took to the streets in rebellion against traditional America. One might find it rather peculiar that in this conservative age, Martin Luther King, Jr. has had such a high profile. Highways, bridges, public monuments of all sorts have been constructed in his honor. A national holiday has been established, and the celebrated civil rights leader has been named an official martyr of the Catholic Church. A virtual library of literature on the era of protest has emerged, with scholars debating the pros and cons of civil rights activism and reform. This book by Clayborne Carson, however, seems to have received less attention than it truly deserves. It apparently was not a best seller, nor did it make the New York Times list of outstanding books for 1998, the year of its appearance. Perhaps this is because of what the book purports to have accomplished. Nominally described as an autobiography, it is in fact the work of Carson and a group of scholars and students at Stanford University. But Carson has the right credentials for the production of this book. A reporter for the L.A. Free Press, whose African American roots and early career brought him into the field of civil rights activism, he became a movement participant and is noted today as an outstanding interpreter of Civil Rights era history. Involved in numerous scholarly projects and associations, Carson developed a relationship to Coretta Scott King in the 1980s, and became the leading figure in the production of the fourteen volume Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., a project of Stanford University in association with the King estate. This volume is thus written and produced with the full cooperation of the King family. Carson’s methods also lend to its authenticity. It is based on the existing published writings from King’s lifetime, with transitional narrative supplied by Carson. The text itself was constructed, based on the condensed and edited writings by King, with verbatim passages rendered in italics. The source material included runs the gamut of documentary materials available through the King papers. Perhaps it is to be expected that in this conservative era, there is on the whole less appreciation for King than during his lifetime. Some scholars have even sought to marginalize King’s influence, selecting other figures, such as Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hammer, or North Carolina’s Robert Williams as more representative of Black America and its freedom struggle. All the more reason why this book should have been produced exactly as it is, and why it deserves our attention today. King was an extraordinary individual who exerted his leadership at a moment that was crucial for America and the South. Assaulted both verbally and physically in the course of his life, he was repeatedly denounced, jailed, and made the object of an ongoing vendetta by his detractors within the highest levels of American government. At the center of leadership in the movement that led to the passage of comprehensive civil rights legislation, King was then assassinated, lionized, and made over into a civil rights icon—who, in the purview of the American media, has in recent years seemed to become more image than reality, a marble man trotted out at the convenience of conservative regimes with which he would have had little or nothing in common. The King autobiography is therefore a vital contribution to the literature on civil rights, and should be read by students, novices and by serious scholars. For those of us who lived through the civil rights years, the vicissitudes of reform still raise many questions, which require our answers. Did King underestimate the intensity of white backlash? Did he misinterpret the complicity of the Kennedys or the mendacity and duplicity of Lyndon Johnson or J. Edgar Hoover? Or, did King’s rivals for leadership among blacks, those who chose to steer the movement away from non-violence down the path of self-defense and retaliation really have it right about the USA? Unlike the conventional biography, this book reflects a disadvantage—it cannot fully reveal the forces arrayed against King and the movement. But what it does accomplish may be more significant. It reveals King the strategist and spiritual leader, who understood the dynamics of political action in a racist society, who consistently sought to build coalitions among diverse groups, and who forcefully challenged the racist South in its most stubbornly held assumptions. King’s creative adaptation of nonviolent civil disobedience, as employed by Gandhi and his followers, enabled the application of Christian eschatology to a social movement. Through religious faith and philosophical conviction King rose above the bitterness and despair so widely experienced among African Americans and made peaceful change into a reality. Conveying all of this and more, King’s autobiography provides a lucid and effective guide for viewing the Civil Rights Movement from the vantage of its key protagonist, understanding its mind and mentality as it confronted resistance, forged alliances, and stirred the U.S. government to action on behalf of reform. Black America has had many leaders, yet among them King stands virtually in a category by himself, rivaled only by Frederick Douglass. No book on King will ever have the final word; yet this book may well be the one book that expresses the summation of King’s career and vision in a single and accessible volume, doubtless much as King would have written it himself had he lived. Finely edited and constructed, The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. is an indispensable source for those who want to understand King and the movement that changed America. The scholarly debate will continue, and yet beside this book, the rest are mere history. In these pages, the spiritual life and energy of King lives on and may yet provide an inspirational force for the betterment of our world. “For now he belongs to the ages.”

—JLG

John L. Godwin is the author of Black Wilmington and the North Carolina Way: Portrait of a Community in the Era of Civil Rights Protest (Lanham, MD.: University Press of America, 2000). |

|

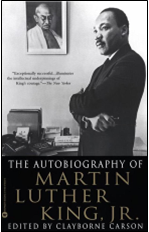

Black America’s Genius of Liberation The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr., Edited by Clayborne Carson, (N.Y.: Warner Books, Inc. 1998) |

|

From The People’s Civic Record Vol. 3, No. 9 September 2003 |